We tend to think of circuit breakers as something ordinary: a switch in a gray box that gets flipped back on after the toaster and microwave gang up on the same kitchen circuit. But in reality, those devices are one of the most important fire prevention tools in your home.

Unlike a fuse that burns out and demands replacement, a breaker resets itself with the push of a finger. That convenience, however, sometimes gives homeowners a false sense of security. Resetting is easy — but knowing why the breaker tripped is where responsibility and safety come into play.

Why Breakers Trip: Not Always Just an Inconvenience

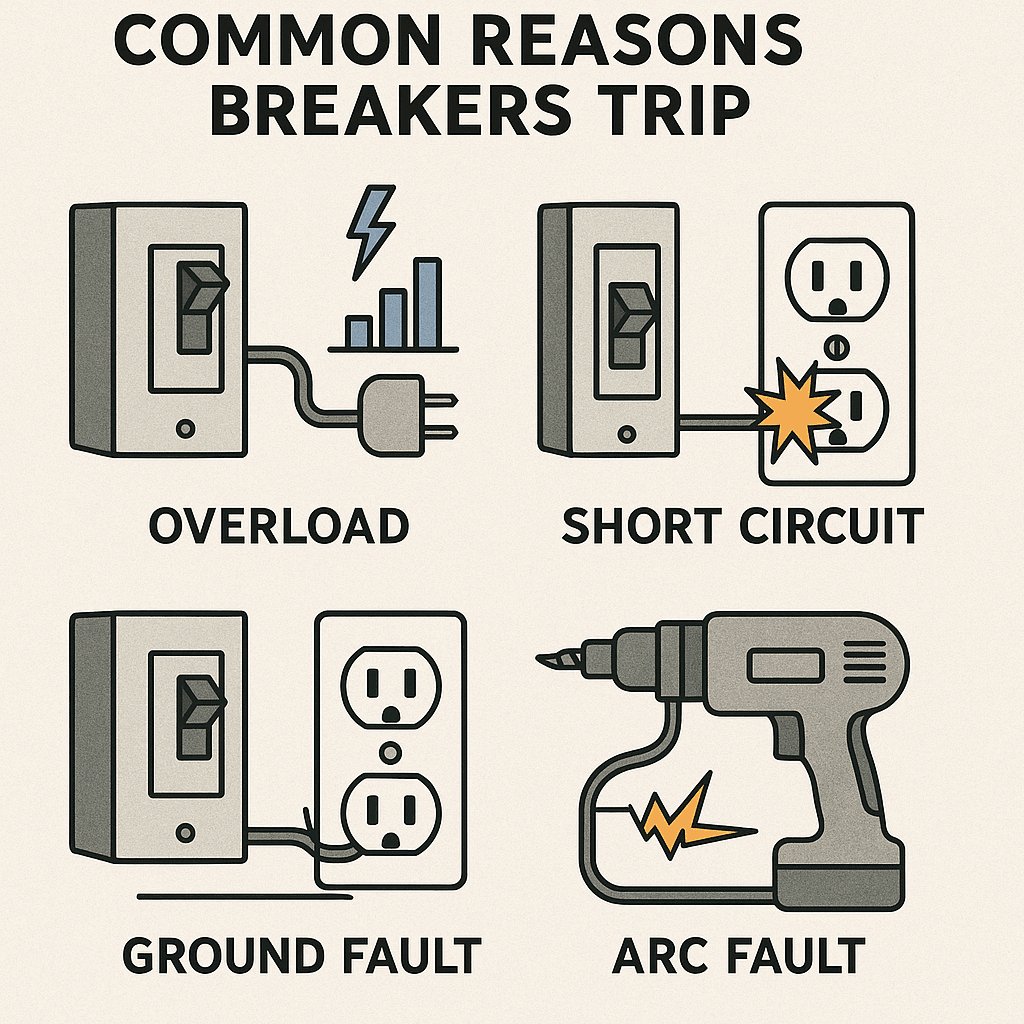

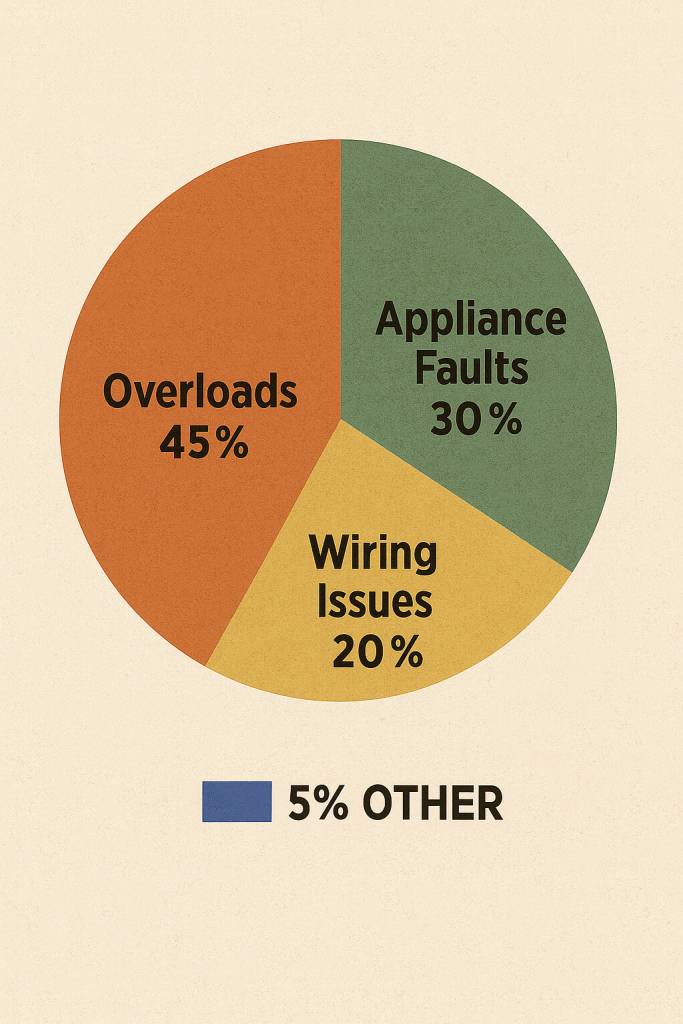

When a breaker trips, it’s telling you something. Either the wiring is overloaded, an appliance is malfunctioning, or there’s a direct fault in the circuit. Too often, the instinct is to immediately flip the switch back on and hope it holds.

But codes remind us otherwise:

- NEC 240.4 mandates proper overcurrent protection sized to the conductor.

- IBC 2701.1 states that all electrical installations must follow the NEC, regardless of jurisdiction.

- California Electrical Code (CEC) echoes the same, with amendments for local conditions.

- California Fire Code 604.3.1 ties it all together by requiring reliable overcurrent protection for emergency systems.

In short: breakers don’t trip for fun. They’re trying to prevent overheating that could start a fire in your wall cavity.

Resetting: A Quick Fix or a Red Flag?

Yes, flipping the breaker OFF, waiting a few seconds, and turning it back ON is usually all that’s needed. But the detail that gets lost in DIY forums is that the breaker must be moved fully OFF before being returned to ON. That resets the internal mechanism.

Manufacturers use different trip indicators:

- Some show a red flag in the toggle.

- Others spring to a neutral center position.

- A few have a push-button that pops outward.

Each is meant to make you stop, notice the trip, and consider why.

If the breaker holds after one reset, fine. If it trips again immediately, you may be dealing with a shorted cord, a fried appliance, or wiring that needs professional inspection.

Replacing Breakers: Straightforward but Not Casual

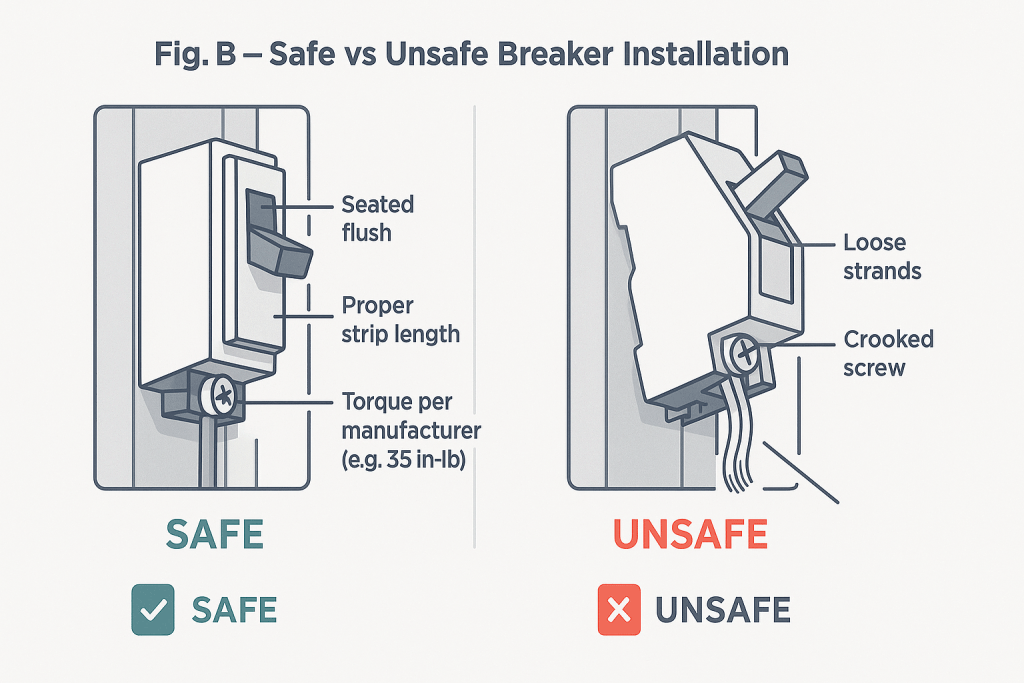

Replacing a breaker looks deceptively easy. A single-pole breaker snaps into the bus bar, a wire slides under the lug, and you’re done. But here’s where commentary from the field matters:

- Service lugs remain live even when the main breaker is shut off. They carry full utility power. Touching them is deadly.

- Many homeowners buy the wrong breaker brand. Square D, Siemens, Eaton, and GE all use different footprints. A mismatched breaker might “fit” but not make proper contact. That’s a recipe for arcing.

- Torque matters. NEC 110.14(D) requires terminations to be tightened per manufacturer instructions. “Hand tight” doesn’t cut it.

From a code standpoint, CBC 2701.1 (per 2025) demands listed and labeled components only. No swap-outs from the bargain bin.

- Left: breaker seated flush, conductor properly stripped, screw torqued.

- Right: breaker half-latched, wire strands loose, screw crooked.

Expanding a Panel: When the Load Grows

Adding a new breaker isn’t just a matter of finding an empty slot. Local jurisdictions (including California’s Title 24 Part 3) require permits for new circuits. Why? Because each circuit adds heat load to the panel, and the panel has a maximum capacity.

Think about modern additions: EV chargers, hot tubs, induction cooktops. Each can draw 30–50 amps on its own. That’s more than entire homes once used in the 1950s.

The NEC 210.11 rule on branch circuits exists because some areas — like kitchens, laundry rooms, and bathrooms — require dedicated circuits to handle modern demand. Installing a 20-amp kitchen circuit is not a suggestion; it’s mandatory.

The Rise of GFCI and AFCI Breakers

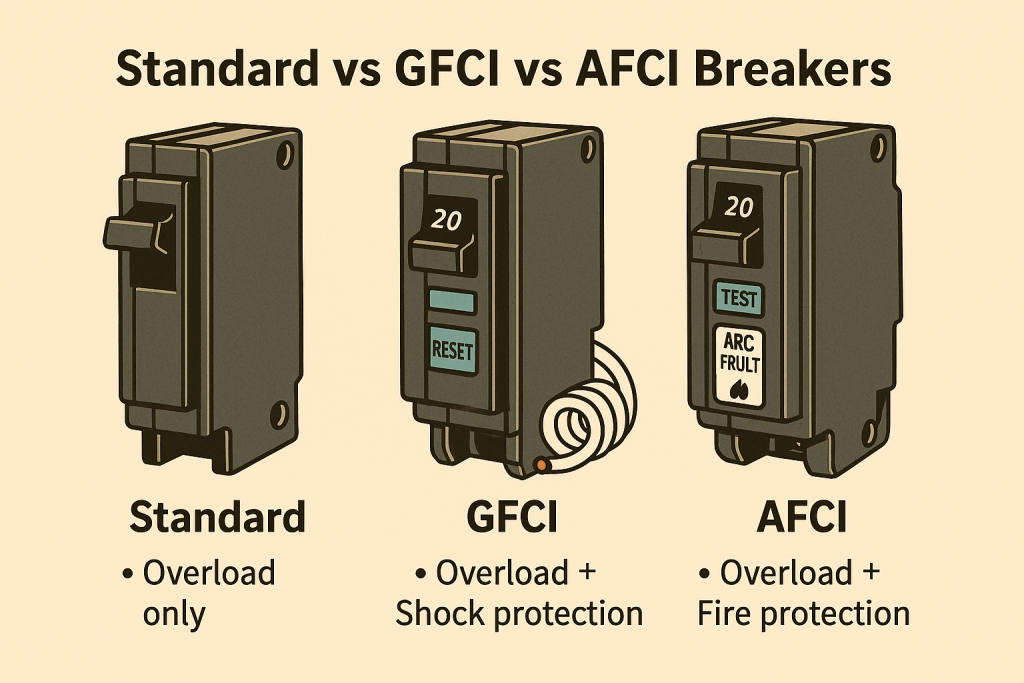

If breakers are the first line of defense against fire, Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters (GFCI) and Arc Fault Circuit Interrupters (AFCI) are the next.

- GFCIs trip when current leaks to ground, preventing shock. NEC 210.8 requires them in wet locations.

- AFCIs sense dangerous arcing, which is responsible for many electrical fires in bedrooms and living spaces. NEC 210.12 covers these.

- California Fire Code adds its own emphasis on emergency power and life safety systems requiring fault protection.

In commentary terms: yes, these devices are more expensive, but they’re also life savers. Anyone remodeling should consider upgrading. The 1999 edition of the National Electrical Code, the model code for electrical wiring adopted by many local jurisdictions, requires AFCIs for receptacle outlets in bedrooms, effective January 1, 2002. Although the requirement is limited to only certain circuits in new residential construction,

[Custom Diagram Placeholder: Fig. C – Standard Breaker vs GFCI vs AFCI]

- Three breakers side by side with callouts:

- Standard = Overload only

- GFCI = Overload + Shock protection

- AFCI = Overload + Fire protection

Professional Advice vs DIY Temptation

As someone who’s seen both clean installs and nightmare panels, the message is simple: know your limits. Resetting a breaker is fine. Replacing one if you’re confident, maybe. But rewiring circuits or adding capacity? That’s where the line is drawn.

Codes exist for a reason: they’re written in blood and ashes from fires past. The NEC, IBC, and California amendments aren’t bureaucratic red tape — they’re collective memory of mistakes that burned down homes.

Suggested Tools & Products

If you’re serious about maintenance but cautious about risk, here are solid starting points:

- Voltage Tester – confirms power is truly off.

- Replacement Circuit Breakers – always match your panel brand.

- GFCI/AFCI Combo Breaker – extra protection.

- Insulated Screwdriver Set – safety first.

- Rubber Insulating Mat – non-conductive work surface.

Strongly encouraged service recommendation: Contact a licensed electrician.

Circuit breakers sit quietly in the corner of your home, often ignored until something goes wrong. But whether it’s a nuisance trip or a full replacement, they’re not to be dismissed. Treat every trip as a message, follow the codes, and respect the hazards.

In the end, electrical safety is less about flipping a switch and more about understanding why the switch exists.

Resources:

- International Code Council -Building Code

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) – an account must be created to view resource <click here>

Author by: GCC Writing Staff

Art/Images by: AI